An overview of all the Inca woodworking machines, and a look at what makes them still so popular today.

Inca was a Swiss company known for their reliable and highly accurate hobbyist woodworking machines. Their machines are still popular today and can be found readily on the second-hand market. Because they are vintage machines, mostly from the 70s to 90s, it can be difficult to find information about them and make sense of all the different models.

This guide will help you get to know most of Inca’s popular machines, such as the Inca Major table saw, Inca Euro 260 band saw, and Inca Automatic jointer planer. You can use the table of contents below to jump directly to a specific category.

Inca was founded early in the 20th century in Switzerland, and started making woodworking machines in the 1930s. It wasn’t until a few decades later, however, that they focused solely on woodworking machines.

INCA stands for Injection Cast Aluminium, which is the technology that sets them apart from most competitors. High-end competitors use cast iron, and low-end ones tend to rely on sheet metal. Cast aluminium has the advantage of being light weight and cheaper to produce than cast iron, but is much more stable and accurate than sheet metal.

The design and production of all these components took place in Switzerland, giving the company great control over quality and reliability of the parts. Combined with the use of cast aluminium, it explains why Inca machines still remain in good shape after decades of use.

Throughout their history, Inca never released more than a few dozen different models of woodworking machines. This is probably one of the reasons why their machines are well made — rather than pump out many different models, they focused on optimizing and perfecting a limited number of machines.

From 1978 onwards, production moved to France. Whether this affected the quality of production is unclear, but there seem to be no serious differences between the Swiss and French machines.

From the 1980s onwards, Inca appears to have gone in a downward spiral, most likely due to competition from cheaper (often Chinese-made) machines in the hobbyist market, and their lack of presence in the professional woodworking market. Inca finally went bankrupt in 2011.

There are three table saws in Inca’s hobbyist range: the Universal, the Compact, and the Major. These are also the ones you are most likely to still find on the second-hand market today. Due to their small size, affordability, and high precision they are popular entry-level machines for beginning woodworkers.

Type of machine

Table Saw

Designed in

Switzerland

User rating (2)

Production status

Vintage

The Inca Universal (US model 150/159) is the smallest of the Inca table saws, with only 55 mm cutting capacity, and a maximum blade diameter of 178 mm. The original motor is only 750 W, which may cause some difficulties cutting thicker hardwoods.

There are a few special things about this machine. Firstly, unlike modern machines of this size, the motor is not integrated. Rather, it is suspended under the table top, connecting to the table saw arbor with a belt and pulley. The advantage of this system is that it is easy to replace the motor with a more powerful new one.

The Inca Compact is essentially the same machine as the Universal, except that it actually does have an integrated motor. This makes it harder to repair the motor, but if it runs fine and your space is limited, it is the preferred machine.

Tip: If you plan to replace the motor, take the pulley sizes into account to make sure the table saw arbor runs at the right rotational speed (see the manual). You can use a pulley calculator to find out what size you need.

The second special, and most unique, thing about the Universal is that the saw blade cannot tilt. Instead, the entire table tilts around the blade. This means the blade will always remain at 90 degrees to the floor, and the table can swivel. There is a locking mechanism with a knob to fix the table in position.

This system is more dangerous and cumbersome to use than modern tilting blades. Because the table is at an angle, gravity will start pulling the workpiece down as you push it through the saw. This increases the chances of kickback significantly. Most users actually refrain from making mitered cuts on this machine. This is a major downside and something to take into consideration when thinking about buying this machine.

Another downside of this machine, besides the limited size and difficulty making angled cuts, is the blade guard. The blade guard itself works fine, but it is attached to a metal bar that blocks you from making cross cuts that are longer than the table is wide. It is not easy to remove this, so you basically have to decide to either always leave it off or on. Leaving it off obviously makes the machine less safe to use.

Tip: If you are missing the riving knife, on the Yahoo Inca Owner’s Group there is a scan with exact measurements that you can use to cut your own riving knife from some sheet metal.

Despite these downsides, the Universal is still an excellent machine if you are aware of its limitations. The fence is very precise, and has a fine-adjustment knob which lets you put it exactly in the right position. The mitre slot is also play-free and the mitre gauge comes with a flip stop.

Combined with the straight cast aluminium table, this lets you make extremely precise cuts that would be difficult to achieve on many modern machines in the same price range.

In addition, there are multiple attachments available to add more functions than just the table saw. There is a tenoning jig, which is widely praised (and because of that expensive on the second-hand market), mortising table, spindle moulding attachment, and sanding station attachment. Some of these are interchangeable with the Inca Major.

Note: The miter slot of the Universal is dovetailed and not suited for modern miter gauges. It is also not compatible with the Inca Major. The miter gauge of the Universal does fit on the Inca Euro 260 Band Saw.

Type of machine

Table Saw

Designed in

Switzerland

User rating (1)

Production status

Vintage

The Inca Major (US Model 250/259) is the larger brother of the Universal. Its size is more suited for most hobbyists, but it shares most of the other flaws of its smaller brother. It has the same tilting table mechanism, making angled cuts dangerous, and the blade guard can be in the way of crosscuts.

Because of its size and increased power, the Major is the better machine for most people. Because of this, it is also about 2 to 3 times more expensive on the second-hand market than the Universal, which tends to sell for just over €100 in Western Europe.

If you find a machine with many accessories present and in great optical shape, expect to pay a substantial premium, because there are some collectors who will drive the price up. Inca machines seem to be significantly more expensive in North America.

In addition to the accessories mentioned for the Universal, there is also a sliding table available for the Major, which also fits on the Inca Master and one of the Spindle Moulders. Another advantage compared to the Universal is the straight miter slot, making it easier to find a modern miter gauge to fit.

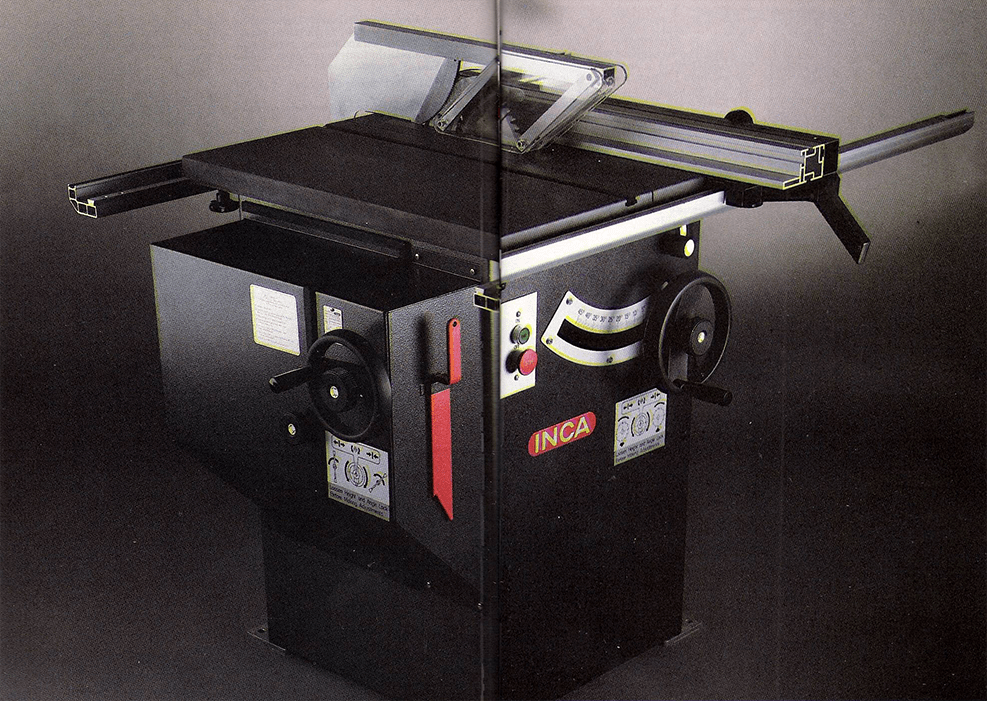

Besides the two small machines we just discussed, Inca also made three cabinet saws, the Master, Supermaster, and Professional. The Master can be seen like an improved and upgraded version of the Inca Major, while the Professional is a truly high-end cabinet saw. The Supermaster is an evolved version of the Master, borrowing some upgrades from the Professional.

The biggest improvement of these three machines over the Major and Universal is that they have tilting saw blades rather than tilting tables. The Master can be seen as the successor of the Major. It is not very large for a cabinet saw, but it does have an integrated stand and handwheels for setting the blade height and blade angle.

The arbor diameter of the Major and Master is the same, so all saw blades fit on both machines. There are also multiple accessories available for the Master, some of which fit on the Major. Among these are a tenoning jig, a sliding table, a mortising table, and sanding station (which is attached to the mortising table). You can see all accessories in this promotional leaflet.

The Inca Professional (US model 2100 and 2200) was a much more high-end and technically advanced machine. It is much more powerful (3000 W motor), has a wider table and extension rails, and a better fence system. It also had scales on which you could exactly read the height of the saw blades.

Like the other Inca table saws, there were several attachments available, like a sliding table. The original version (US model 2100) had a cast aluminium table, but there may have been improved versions (possibly US model 2200) that had cast iron tables.

The Inca Supermaster — probably the table saw with the coolest name — is very similar to the Master, but was improved with the extension rails and longer and more sophisticated fence of the Professional.

There are four machines in Inca’s jointer-planer combination series. There is the original small Inca Jointer Planer, which was unique because of the planer being an attachment on top of the jointer tables. Then there is the most popular machine, the Inca Automatic (US model 510 to 570), which has the classic jointer planer design with automatic feed rollers.

The last two machines are very rare and much less well known, namely the Inca Concorde 315, and the Inca Professional 4000. These machines are much larger and have an integrated stand, instead of a table with a motor hanging underneath it. We’ll take a look at each of these machines.

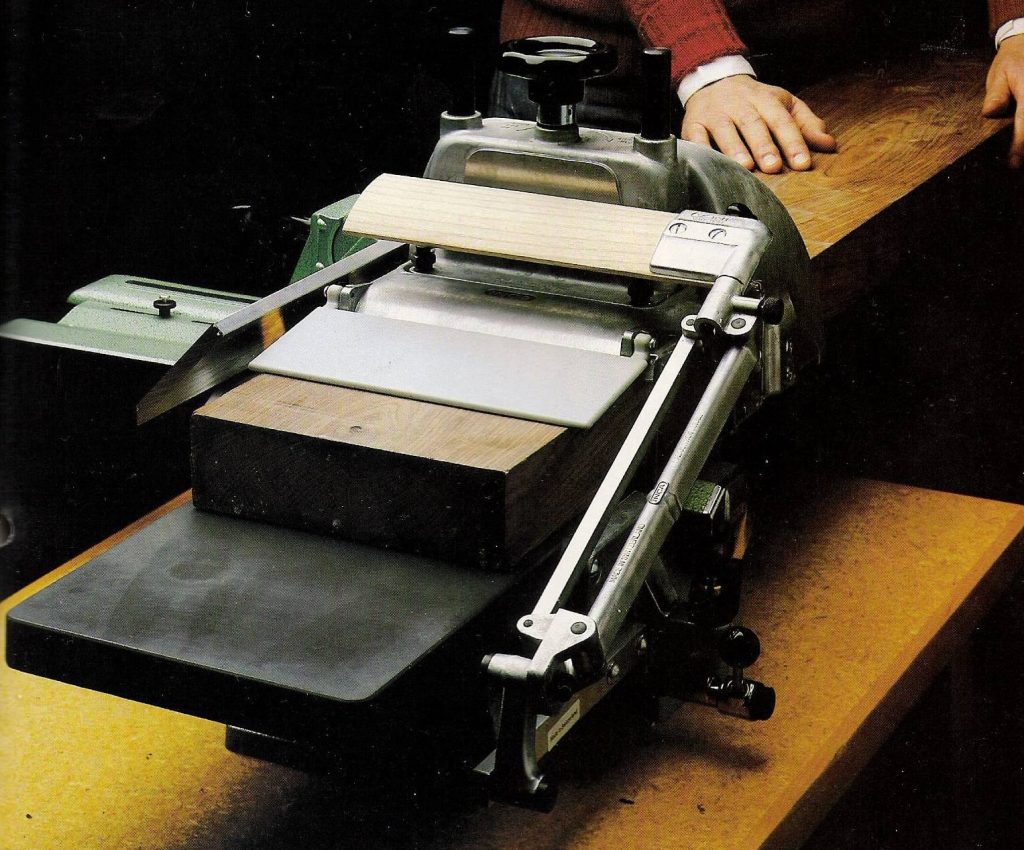

The classic Inca Jointer Planer stems from before the second World War, and remained in production for a long time, which may be an indication of its quality. It has a maximum jointing width of 220 mm, and like the Inca table saws, it is powered by a motor suspended underneath the table, powering the arbor with a belt and pulley.

It is a very barebones, basic jointer, but very precise and robust. Because there are so few parts, and those parts are made of quality materials (cast aluminium tables), they can deliver excellent results even today. All that is really needed to restore an old machine is to replace the ball bearings.

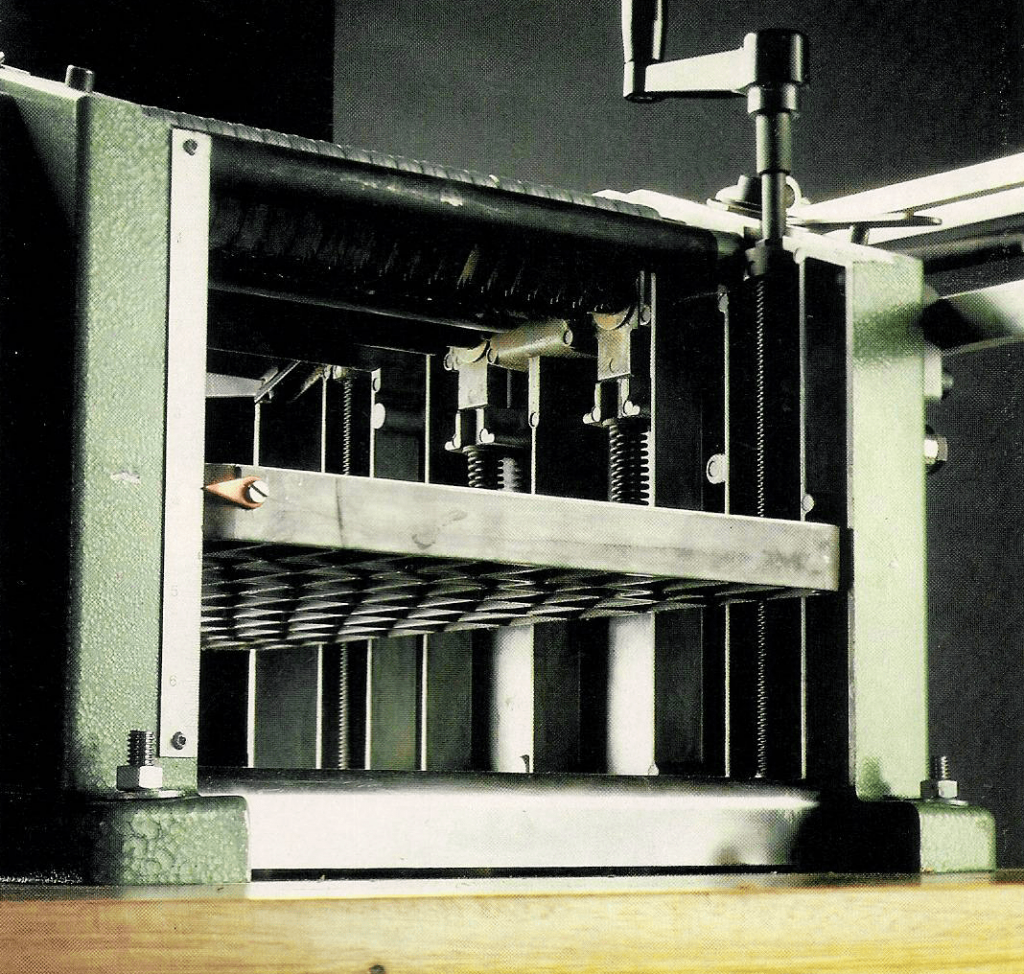

The unique thing about this machine is that the planer component is mounted on top of the jointer tables, not underneath them. The attachment has metal spring plates pushing the workpiece upwards to keep it in a straight position.

It is a bit finicky to get it set up right, but once you do, you can get great results with it. You have to push the wood through the machine manually, which requires quite a bit of effort. So don’t expect this machine to be a breeze to use, but if you are willing to put in some effort, good planing results are definitely possible.

Tip: The thickness planing attachment is rare and has a big impact on the price of the machine. Take this into account when making a bid.

There are two main version of this machine: One with set screws in the arbor, and one without them. It is quite a lot of effort to set the planer blades up without set screws (but doable), so think twice about buying a machine that is missing the set screws. There was also a version with a rabbeting ledge.

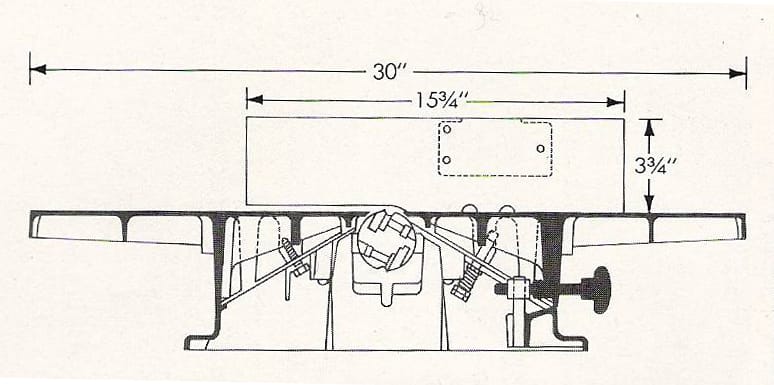

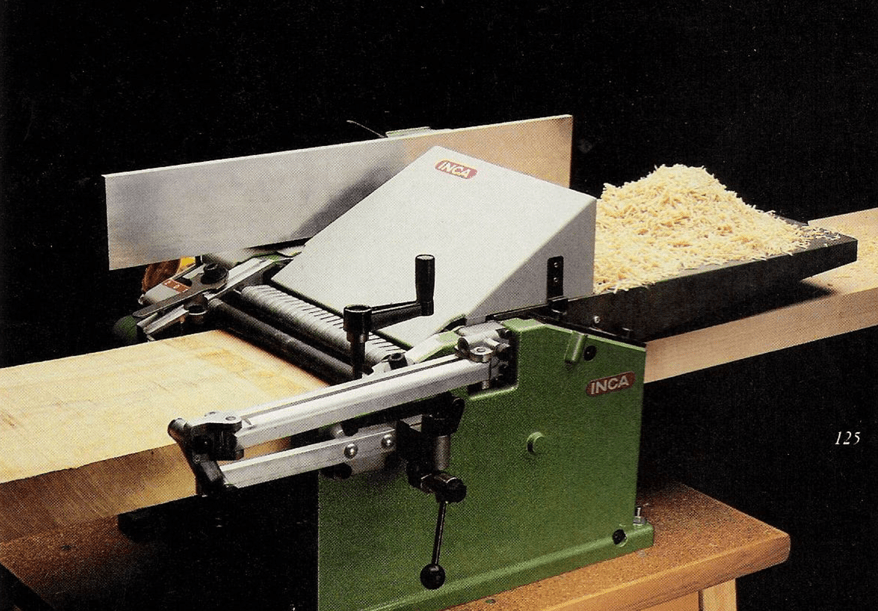

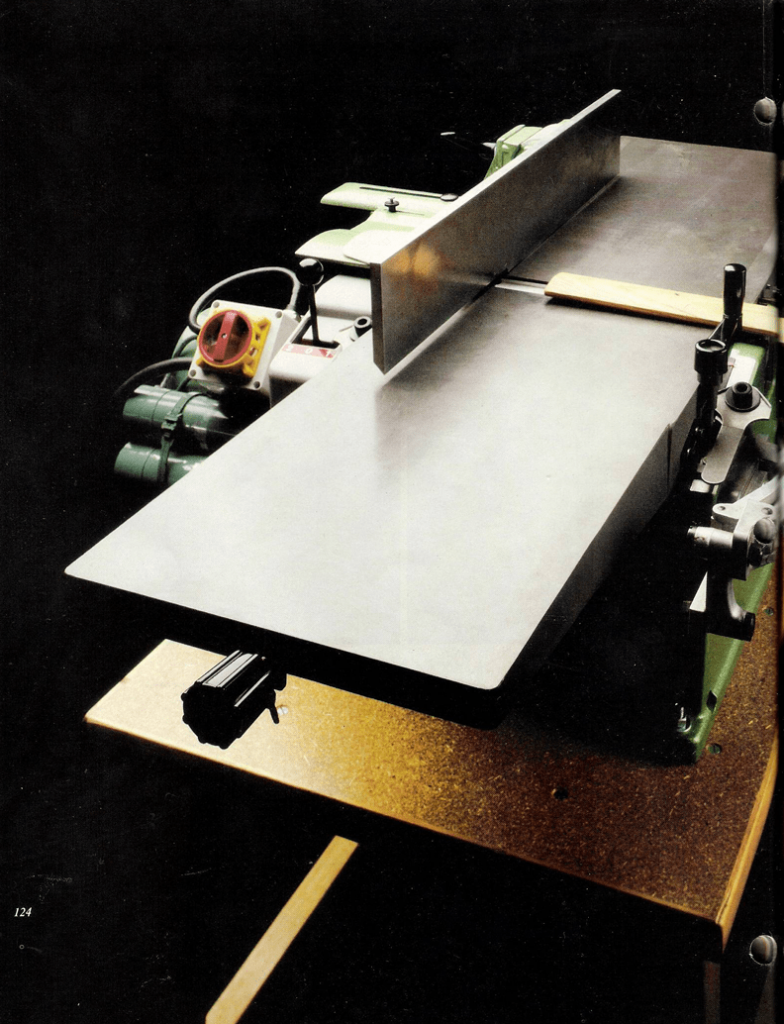

The Inca Automatic Jointer Planer (US model 510 to 570) is the most common machine of all the Inca jointer planers. It is better than the old jointer planer in multiple ways. It is larger, with 260 mm jointing capacity, and the planer is integrated in the machine — and as the name suggests, the throughput is no longer manual, but feed rollers pull it through automatically.

There are two models, one more common in Europe (the 343.190.01), which has the motor hanging under the table, and one more common in North America (the 343.190) which has the motor mounted on the side. This takes a bit more space horizontally, but it does allow you to place the machine on any worktop instead of having to have an entire table.

What sets the Automatic apart from competitors from the same era and price range is the use of quality materials. Besides the cast aluminium tables and frame, Inca also used brass for some essential moving/gliding parts to ensure smooth movement. The only weak spot is the use of plastic for some of the gears of the feed roller mechanism.

Tip: Some users have connected a separate motor to the feed system, which means less chance of breaking and manual control over the feed speed.

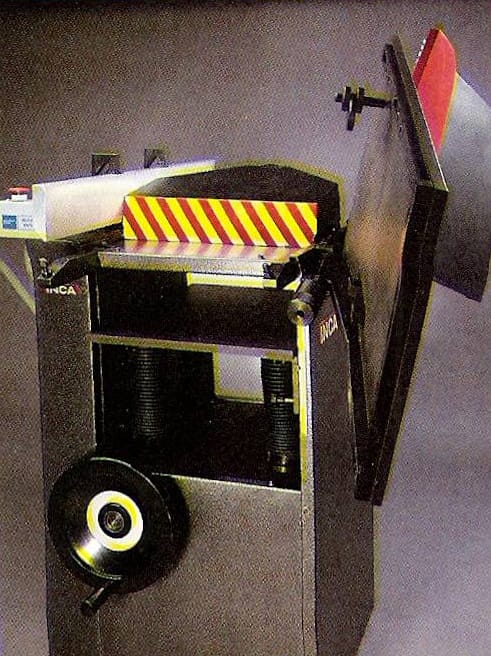

The final two jointer planers made by Inca are the Inca Concorde 315 and the Inca Professional 4000. These are very rare and not that much is known about them other than their specifications. But if these are up to the traditional Inca standards they should be quality machines and a good purchase if you can get them for a decent price.

The main differences with the Automatic are that these two machines are completely stationary. Their stands are integrated, making them more stable and robust. They also have larger capacities (315 mm and 400 mm respectively) for jointing and planing. They were likely aimed at professionals instead of the traditional hobbyist market.

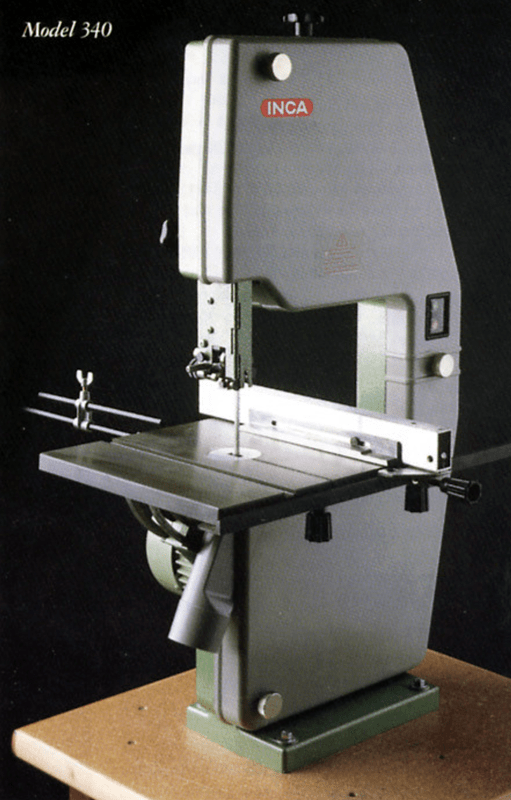

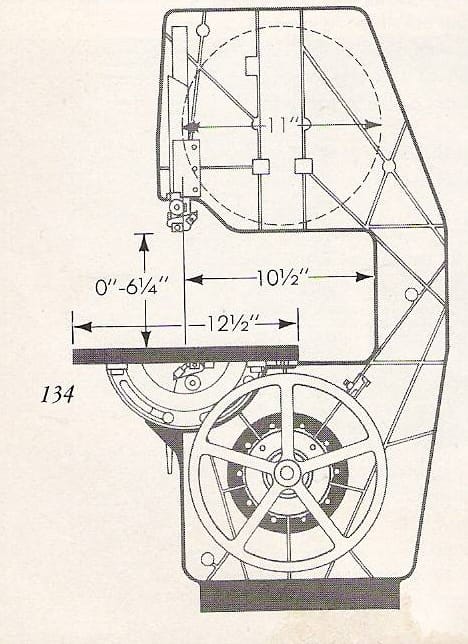

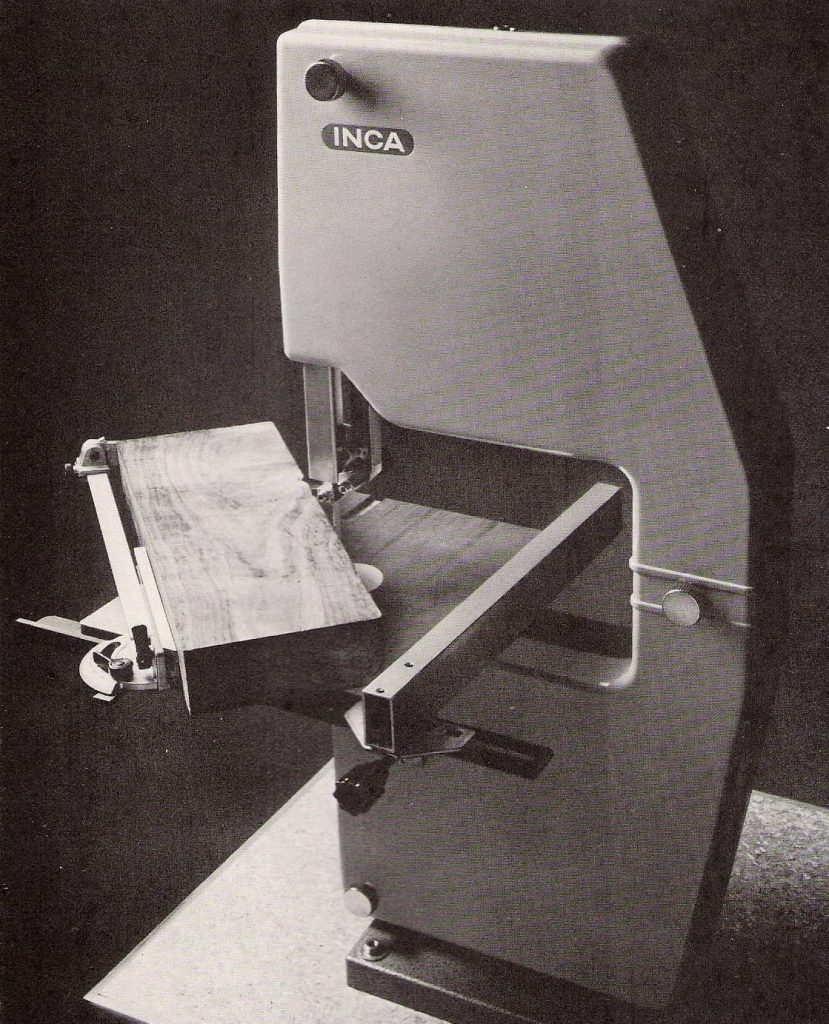

Inca made three band saws, the Inca Euro 260 (US model 310/320/330/340), the larger Inca Expert 500 (US model 710), and the much more unknown, and smallest, Inca Euro 205. The Euro 260 can be found more often on the second-hand market today than the Expert 500. These saws are excellent little machines and a great example of Inca’s precision and reliability. The Euro 260 band saw (shown in the images below) is in fact our favorite machine of the entire Inca range.

The band saws are mostly made of cast aluminium, while the removable side (to change the blades) is made of plastic, which is sometimes white and sometimes green, depending on your machine.

There are three key differences between the Euro 260 and the larger Expert 500. The latter has a more powerful engine and bigger cutting capacity, and it has three wheels instead of two. Because of the three wheels the saw blades are more strongly curved, which makes them wear out and potentially break more quickly.

The basic designs seems to have remained mostly the same over time. There have been some improvements of later machines over earlier ones. Some machines lack a dust port, and sometimes the on-off switch is inconveniently located on the motor rather than on the side of the frame.

The original Inca band saws came with metal guides, but many users seem to replace them with special hardwood blocks instead. There are also special guides for extremely thin band saw blades, but these are quite rare.

The Inca Euro 260 has an aluminium fence and a miter slot, in which the miter gauge of the Inca Universal table saw fits.

Tip: If your Inca Euro 260 is missing the rip fence, Axminster in the UK sells one that fits perfectly (we’ve used this ourselves). You just need to drill some holes in the rail to fit it to the table. It should cost around £20.

What makes these band saws great is their excellent precision and reliability, while remaining affordable. On the European market the Inca Euro 260 tends to go for prices between €200 and €300. They may be more expensive in North America. Comparable new machines in this price range are usually plastic and much less reliable.

The only downside to the Inca band saws is the lack of modern features, such as a quick release toggle for the blade tension, but these are not essential. The Euro 260 is somewhat limited in power as well, so don’t expect to use it for resawing thick boards.

Note: Inca Band Saw Blades need to be welded the other way around compared to most normal band saw blades. Any shop that produces band saw blades will be able to do this for you. If you mention the brand Inca to them, there is a good chance they know about this peculiarity.

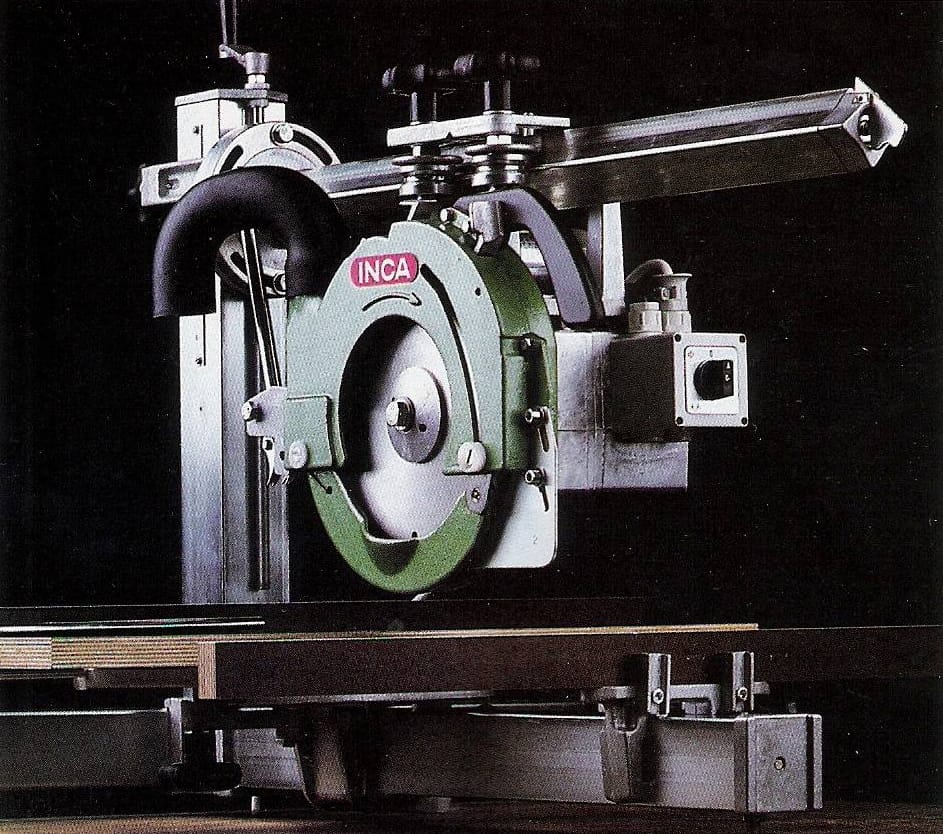

We’ve covered most machines in this article, but Inca made a few more. The most interesting of these was the Reverse Radial Arm Saw (see image), which worked the way its name suggests — to cut you had to push the saw blade away instead of pulling it towards you. It was originally designed as a gift from the employees to the company president. The Austrian company Eumenia also made a nearly identical Radial Arm Saw, which is more common. Although an interesting piece of engineering, the machine was somewhat flawed and never took off.

Inca also made lathes and spindle moulders, which we will try to add to this article once we have found sufficient information about them.

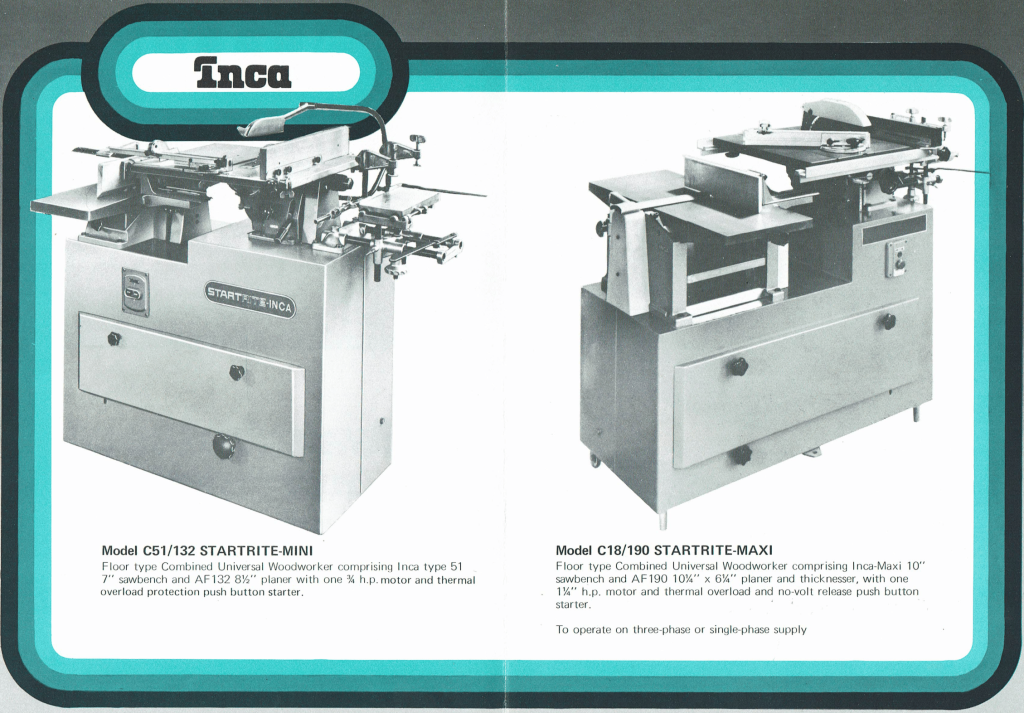

UK manufacturer Startrite made some interesting all-metal stands for single and combinations of Inca machines. For example, they made a Maxi-Joiner stand for the Major Table saw and Automatic Jointer Planer. These stands are still quite popular on the (European) second-hand market and fetch quite a premium.

You can browse old brochures of Startrite INCA combinations here.

There are three main sources of information about Inca machines. There is the user-operated Inca Owner’s Group, where you can ask questions and find many images of repairs and upgrades of other Inca owners. Then there is the Inca Blogspot page, where you will find tons of old catalogues, manuals, as well as a bit of history about the company. And finally there is Doebeli.ch, who have made most manuals and part lists and numbers available.

Doebeli also own original parts, which you can still order today, but note that these are not cheap and have to be shipped from Switzerland. If you are in North America, you are probably better off contacting Eagle Tools in Los Angeles, who used to be an Inca dealer and still have spare parts as well. Alternatively there is Inca Machines in France, who, besides spare parts, also sell refurbished original Inca machines.

Doebeli sold their stock of Inca parts and machines to another Swiss company called Inca Maschinen.

You can now find all of the manuals that used to be on Doebeli on the Inca Maschinen website.

The new owner also repairs, refurbishes and sells used Inca machines.

Hopefully this guide helped you get to know Inca woodworking machines a bit better. If you have any useful info or tips about these excellent little machines, feel free to share them in the comment section below.

© Machine Atlas 2026

A comment on the blade guard arm getting in the way when crosscutting with the Inca Major table saw (341.018). The whole guard can be dropped to the front of the saw (resting on the sawdust chute) by loosening the knob at the base of the saw and swinging the whole apparatus down and out of the way.

I see, I think the same holds for the Inca Compact, but I found that such a hassle (knob not easy to loosen and not in a convenient place) that I didn’t think to mention it. Is it easier on the Inca Major?

I bought the Major with the sliding table, extra long rails, mortising machine, etc. in 1978 or 1979 and have worked it like a rented mule ever since. It’s a wonderful for fine work on wood, but awkward for plywood. One of the easiest saws I’ve ever used for quick 1/100th of an inch adjustments. It would never have occurred to me to describe it as a “hobbyist” saw. Also, it’s the only high-quality saw I’ve ever used that is light enough for one person to move around and even load into a truck alone. I think it’s unbeatable at any price if you work small. It would be my first choice by far for model making, etc.

I own an Inca Major with an aluminum top. The table top tilts and can cause the safety issues mentioned here. However, if you use a crosscut sled for miters and clamp your piece down, it does not drop into the blade, while the cutoff piece falls to the floor. I find that when I cut miters on my tilting auger cabinet saw, the smaller cutoff pieces fall into the sled gap and into the the blade. So the tilting table is actually safer (if you use a sled and clamps). Sadly, magnetic featherboards don’t work on aluminum, so I wish my top was cast iron. The microadjusters and other accessories are fantastic!

I own a number of Inca machines among them the Automatic 570 the Major 259 of which I have had two and sold one; the 205, 340 and 710 bandsaws and the rare Inca dust collector. I believe that at the time Inca was marketed in the US as a boutique type tool line. Clearly it is not. It is a well designed tool that often time has been vilified by those who hate it and loved by those of us who cherish them.

The Major is a “joinery saw” it is not intended to cut sheet plywood and neither is the Delta Unisaw. For that there are such machines as the Altendorf F45 or the Martin or Beam saws etc. etc. Someone else commented that these are great tools for model makers and this is true. I have been in the cabinet business for the past 40 years and owned the Altendorf the Weekee the Homag and SCMI and a few other monster machines but I find nothing more relaxing than working with my Incas.

I own an Inca 343.190 joiner/planner and live in Atlanta, Ga. I am searching for some technical support to help me determine why the round drive belt is coming off when I feed wood through the planner. Please give me some advice.

Hal

Hi Hal, a drive belt coming off could have multiple reasons, either it’s not being tensioned properly. Or if your blades are dull, or the planer bed is sticky it might jam the feed system, which in turn causes the drive belt to come off.

I would recommend posting a picture or video of your problem on the Inca User Group. I’m positive there will be some people who can help you out with your specific problem.

I have a band saw that’s exactly like the Inca euro 260 it’s called the woodstar 2 can you tell me anything about it

Regards Kevin

Hi Kevin, I think the Woodster is a machine made all the way at the end of the Inca company’s life. It was probably made in France, but I’m not sure if it was made by Inca (or Kity) themselves, or if they licensed out the design. In any case, as far as I know it is identical to the Inca Euro 260. So any info about the Euro 260 also applies to your Woodster II.

Hope that helps.

Thanks rob, that is Very helpful

Cheers Kevin

Hi there. Could the owner of this page please contact me via email. I started a Facebook group for inca woodworking machines and would like to use some of these photos